Hohenschwangau

In Germany, early romanticism is inseparably linked to the development of a new identity, one that seeks to unify the personal, poetic and public selves -- or at least attain some kind of harmony between them. To me, the castle of Hohenschwangau is the most striking (and oddly endearing) architectural manifestation of this effort.

In December of 1805, Bavaria became a Kingdom. After his defeat of the Holy Roman Empire (and just prior to his signing it out of its thousand years of existence) Napoleon elevated some of his allies in Germany to Kingdoms, and thus the old Wittelsbach Prince-Elector became King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria.

|

Long after Napoleon’s star fell, Bavaria lingered on as a kingdom. Caught between the ambitions of the two greater Germanic powers, Prussia to the North and Austria to the Southeast, Bavaria saw itself as the protector of local Germanic identities, all those little kingdoms that had been teased out of the fabric of the old Empire and were left to fend for themselves during the long 19th century.

The creation of a new, regional German identity was a necessary undertaking of the Wittelsbach rulers of Bavaria. |

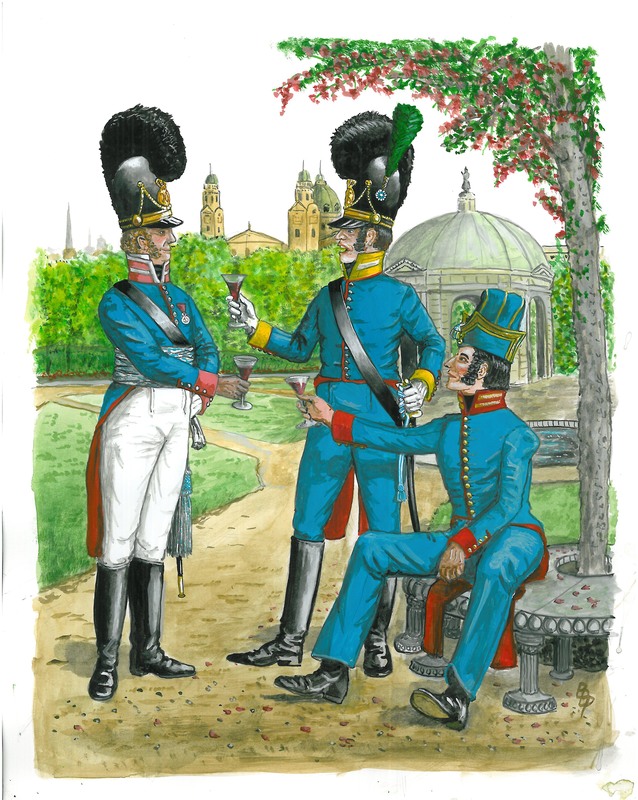

Bavarian Infantry Uniforms, ca 1813

|

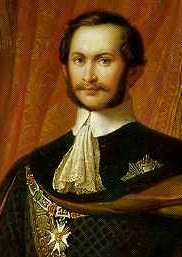

In 1829, 17-year old Maximillian was embarking on his wanderjahr along with his brother Otto. Maximillian was the grandson of old Maximillian I, the elector whom Napoleon had made the first king of Bavaria back in 1805, and he was heir to the Bavarian throne.

|

Young Max’s father, Ludwig, was an enthusiast of the arts and considered one of his chief roles as King of Bavaria to be architect-in-chief; he oversaw the construction and refurbishment of dozens of palaces, monuments and royal residences.

(My favorite of his building projects reflected one of Ludwig’s other passions – beautiful women. In one wing of the refurbished Nymphenburg palace, he established the Schönheitengalerie, in which he kept portraits of the most beautiful women in Bavaria). |

Some Bavarian lovelies, from Ludwig's slightly skeevy Schönheitengalerie

|

|

Ludwig’s aesthetic tastes were Hellenist – he was an enthusiast of the arts of ancient Greece and the Italian Renaissance, and thus the destinations of his young sons on their wanderjahr were to include Italy and Greece.

(Otto, Maximillian’s younger brother, apparently made quite an impression while in Greece: in 1832 he became Greece’s first modern King. One of the chief exports of all those poor small German states throughout the 19th century was, in fact, monarchs. The Saxe-Coburgs were the Bavarian’s chief rivals in this regard…). |

|

But on their way south, young Maximillian spied an old ruined castle atop a small hill overlooking an alpine lake. It was right one the edge of the Alps, in fact: to the north were the rolling green foothills, but immediately to the south -- just on the other side of the small lake – arced up the vast, snow-clad peaks.

It was a landscape perfectly suited to be a backdrop. At least Maximillian must have considered it so, because before leaving Germany to continue his journey south, he purchased the old ruin for 7000 guilders. And for the rest of his journey through the classical world south of the alps, sketches of the palace he would build there, overlooking the Alpensee, filled his notebooks.

|

Andreas Hofer and Josef Hormayr, bold heroes of the Tyrolese Uprising...

|

Upon his return, Maximillian assembled an unusual group of advisers to help him think through the design and reconstruction of the old ruin. One of these was Joseph Hormayr, an Austrian who’d been secretary to the Archduke Johann. Hormayr was a first-generation Romantic nationalist, somebody who felt that regional cultures should inform political power – and as such, he’d actually led the Tirolese in their uprising against French-backed Bavaria in 1809. Neither Maximillian nor Hormayr seemed to hold a grudge, however, and by 1832 the two were working together to plan a building which would be the perfect reconciliation between the state and the individual, between public and private man.

|

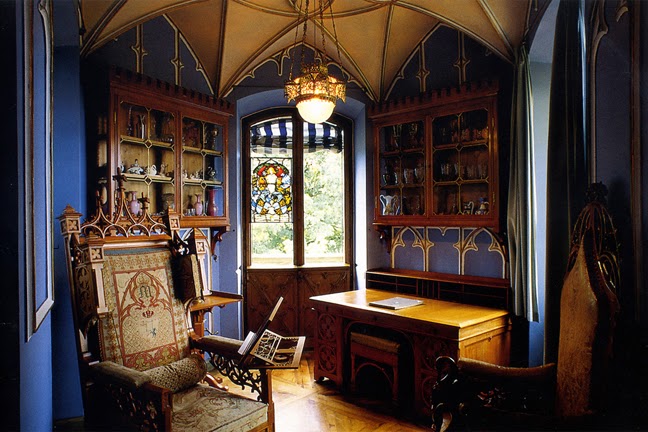

As I’ve written elsewhere, castle-reconstruction was a profound political and cultural act during the 19th century in Germany. Rebuilding an old dynastic ruin could be for purely political purposes (as was the case with Burg Hohenzollern), or it could be a purely personal endeavor (as was Neuschwanstein for Maximillian’s son King Ludwig II). Maximillian’s castle, however, would attempt to synthesize the political and the personal. It would be a private residence, where he and his family would live (for part of the year, anyway); but it would be open to the public from the very beginning. Artists and intellectuals would be invited to stay, members of the public could visit. It would be a structure actively shaping not only the imaginations of its royal denizens, but of its public as well.

Hormayr and Maximillian had a new idea. Paintings would decorate the interior, and the subject of these paintings would be taken from Bavarian history, from local folklore and legends, and from the history of Maximillian’s own family, the Wittelsbachs. State and family histories, folkloric and literary legends: the term Hormayr coined for Maximillian’s use was “poetic moments in history.” The characters and the events depicted would have an aesthetic power, shaping the self-conceptions of those wandering its chambers.

A mural in the "Berchta" room, recounting the birth of Charlemagne

And these images would not be painted on canvas, to be moved or removed at the whim of some future inhabitant of the castle: they would be murals, part of the structure of the place itself. They would be the castle walls.

Another view of the Berchta room

A slideshow of some of the murals depicting "poetic moments" in Bavarian history

I found, when I finally visited Hohenschwangau several years ago, that I preferred this castle to all of the other 19th century re-imaginings and re-purposings of Germanic history. It is small, and open to the beautiful world around it. It does not imply the imperial might that the fortress Hohenzollern does, nor is it a retreat into the personal fantasies that shadow the walls of Neuschwanstein.

The Authari room (Authari was a king of the Langobards, and in theory one of the founders of a kingdom associated with Bavaria

The interior of Hohenschwangau is built on an intimate scale

The murals are beautiful and urge you to learn their stories, but the view of the world outside each window draws your gaze, too. Inside and outside achieve a symmetry, at least, and for a few moments I can imagine that romantic dream of a Unified Self realized, here within these walls.