Romanticism and German Identity

In the early 19th century, to be “German” was an ontological problem.

The term “German” had a number of different meanings, but none fixed. And yet the term “German” was nevertheless becoming crucial in defining an identity for several million central Europeans.

There was no concrete political reference for the term. There was no German state. There was the old Holy Roman Empire, which for a thousand years had provided a loose set of relationships between the hundreds of small principalities, bishoprics and free cities that speckled central Europe. But in 1806 Napoleon had willed even this vague polity out of existence, carving out new kingdoms in the west (the Kingdom of Westphalia in 1807) and “liberating” old / new kingdoms in the south (Bavaria and Baden Wurttemburg).

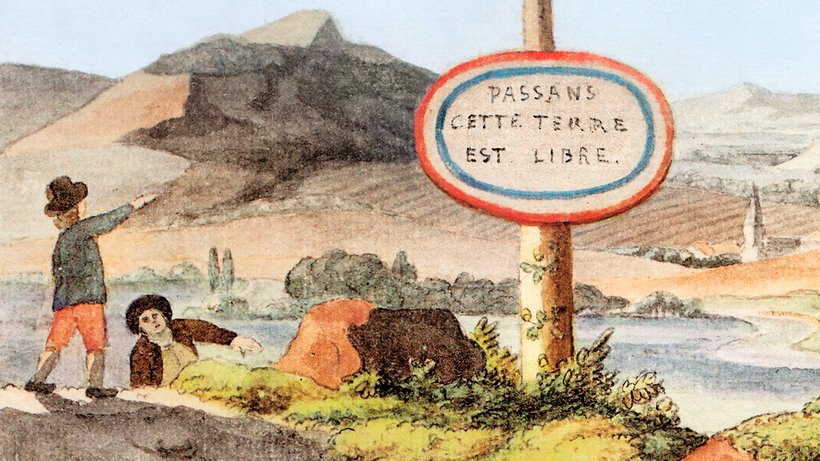

And there was no single epistemological reference for the term “German.” In the heady early days of the French revolution, many intellectuals saw their “Germanness” as a means of freeing themselves form the despotisms of petty princes and bishops and joining a new international brotherhood of reason and equality. (For a brief time in the 1790’s the city of Mainz on the Rhine established itself as an independent republic, and “liberty trees” began replacing statues of princes in the centers of towns along the Rhine; in 1793 Joseph Gorres and city fathers of Mainz sent delegations to the revolutionary government in France, seeking its protection. Here, to be “German” meant to be part of an international brotherhood of reason, overseen by the French revolutionaries)

The term “German” had a number of different meanings, but none fixed. And yet the term “German” was nevertheless becoming crucial in defining an identity for several million central Europeans.

There was no concrete political reference for the term. There was no German state. There was the old Holy Roman Empire, which for a thousand years had provided a loose set of relationships between the hundreds of small principalities, bishoprics and free cities that speckled central Europe. But in 1806 Napoleon had willed even this vague polity out of existence, carving out new kingdoms in the west (the Kingdom of Westphalia in 1807) and “liberating” old / new kingdoms in the south (Bavaria and Baden Wurttemburg).

And there was no single epistemological reference for the term “German.” In the heady early days of the French revolution, many intellectuals saw their “Germanness” as a means of freeing themselves form the despotisms of petty princes and bishops and joining a new international brotherhood of reason and equality. (For a brief time in the 1790’s the city of Mainz on the Rhine established itself as an independent republic, and “liberty trees” began replacing statues of princes in the centers of towns along the Rhine; in 1793 Joseph Gorres and city fathers of Mainz sent delegations to the revolutionary government in France, seeking its protection. Here, to be “German” meant to be part of an international brotherhood of reason, overseen by the French revolutionaries)

Later, after Napoleon’s defeat of Prussia and the old Austrian Empire, the same thinkers envisioned a “pan-German” state that would be the basis of a new republicanism, a utopian elevation of a people above the conflicts and tyrannies of little kingdoms. The Prussians sought to usurp that idea and become the custodians and new despots of such a pan-German state.

As a linguistic and cultural concept, the term “German” was equally intangible. The German language has always been made of a wide range of dialects, different enough from each other to be the basis for considerable misunderstanding, cultural pride and one-upmanship. And the cultural fabric at the time was pretty loosely-knit; the old trading families of the protestant North didn’t have much in common with a Bavarian farmer’s world.

And so, in the early 19th century, the meaning of the term “German” was in flux; powerful forces sought to appropriate the term and use it shape the identity of a huge population in central Europe and beyond.

I’m interested in this period because rarely has the identity of such a wide group of people been so totally up for grabs, subject to political and cultural pressures. And in this competition to define an identity, scholars and writers, artists and philosophers, princes and politicians, all had a hand. Rarely has there been a time in recent European history when an individual faced such a diversity of heady and terrifying possibilities for self-creation.

In this section I’m going to examine some of the different ways some wildly creative people sought to define the concept of Germanness, and build a world.

As a linguistic and cultural concept, the term “German” was equally intangible. The German language has always been made of a wide range of dialects, different enough from each other to be the basis for considerable misunderstanding, cultural pride and one-upmanship. And the cultural fabric at the time was pretty loosely-knit; the old trading families of the protestant North didn’t have much in common with a Bavarian farmer’s world.

And so, in the early 19th century, the meaning of the term “German” was in flux; powerful forces sought to appropriate the term and use it shape the identity of a huge population in central Europe and beyond.

I’m interested in this period because rarely has the identity of such a wide group of people been so totally up for grabs, subject to political and cultural pressures. And in this competition to define an identity, scholars and writers, artists and philosophers, princes and politicians, all had a hand. Rarely has there been a time in recent European history when an individual faced such a diversity of heady and terrifying possibilities for self-creation.

In this section I’m going to examine some of the different ways some wildly creative people sought to define the concept of Germanness, and build a world.