The Printed World, part 2:

Merian's Topographia Germaniae

Between 1640 and 1660 (or so) a remarkable series of books was published. A Frankfurt publisher named Matthaus Merian began issuing volumes of a work called Topographia Germaniae.

Though Matthaus Merian came from a patrician family in Basel, he was trained in copperplate engraving from an early age. He spent his young adulthood studying and working throughout France (Strasbourg, Nancy, Paris), eventualy winding up in Frankfurt where he began working for the publishing house of Johann Theodor de Bry (whose father had been a legendary traveler and engraver himself, one Theodor de Bry).

Merian married his employer’s daughter, Maria Magdelena, and when his father-in-law died he took over the publishing house.

Merian married his employer’s daughter, Maria Magdelena, and when his father-in-law died he took over the publishing house.

Merian established his reputation by making forays into two of the new genres that the printing press had made possible and popular: books of Emblems and what might be called “cartographic illustration” (I’ve written about the development of these genres here).

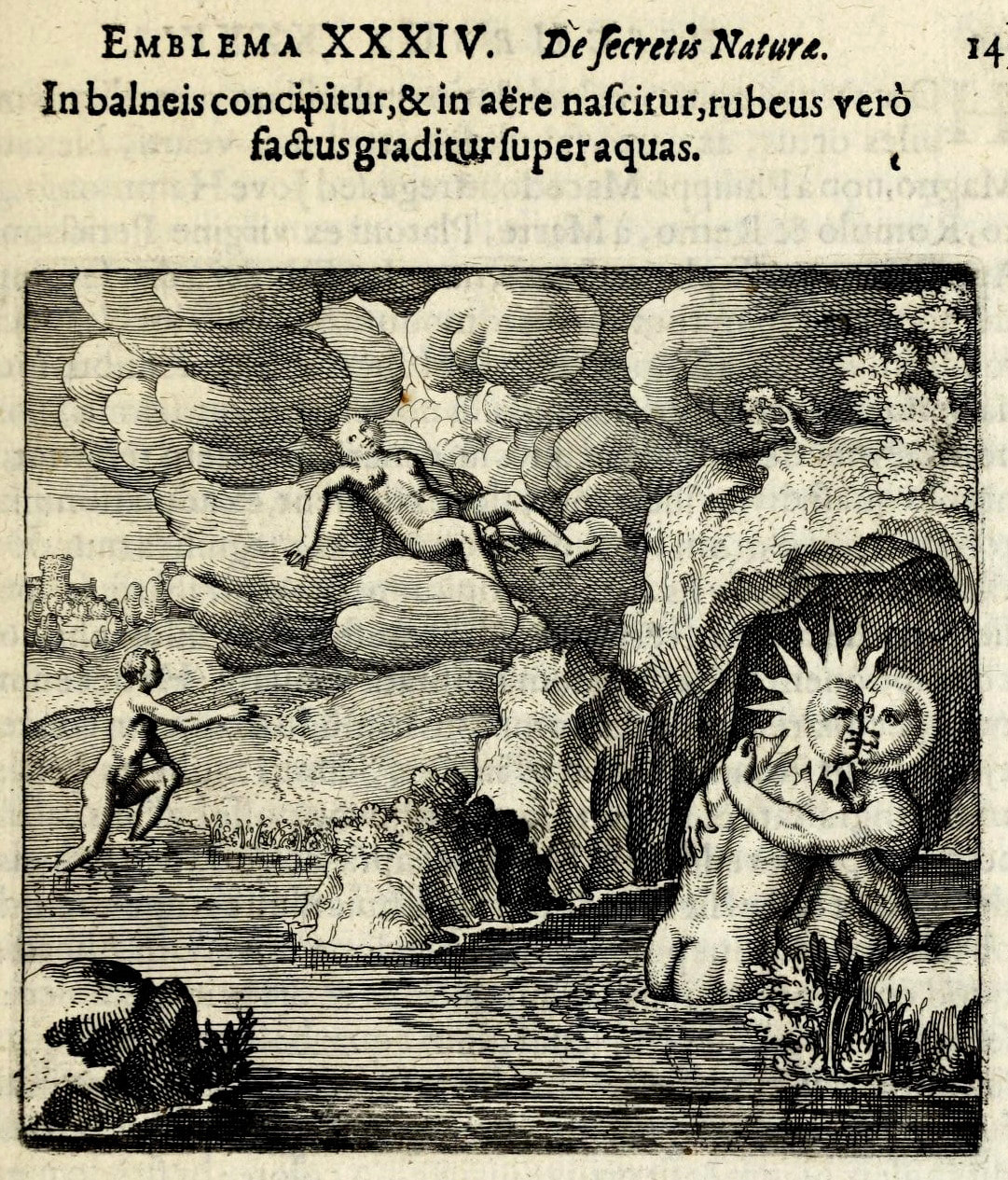

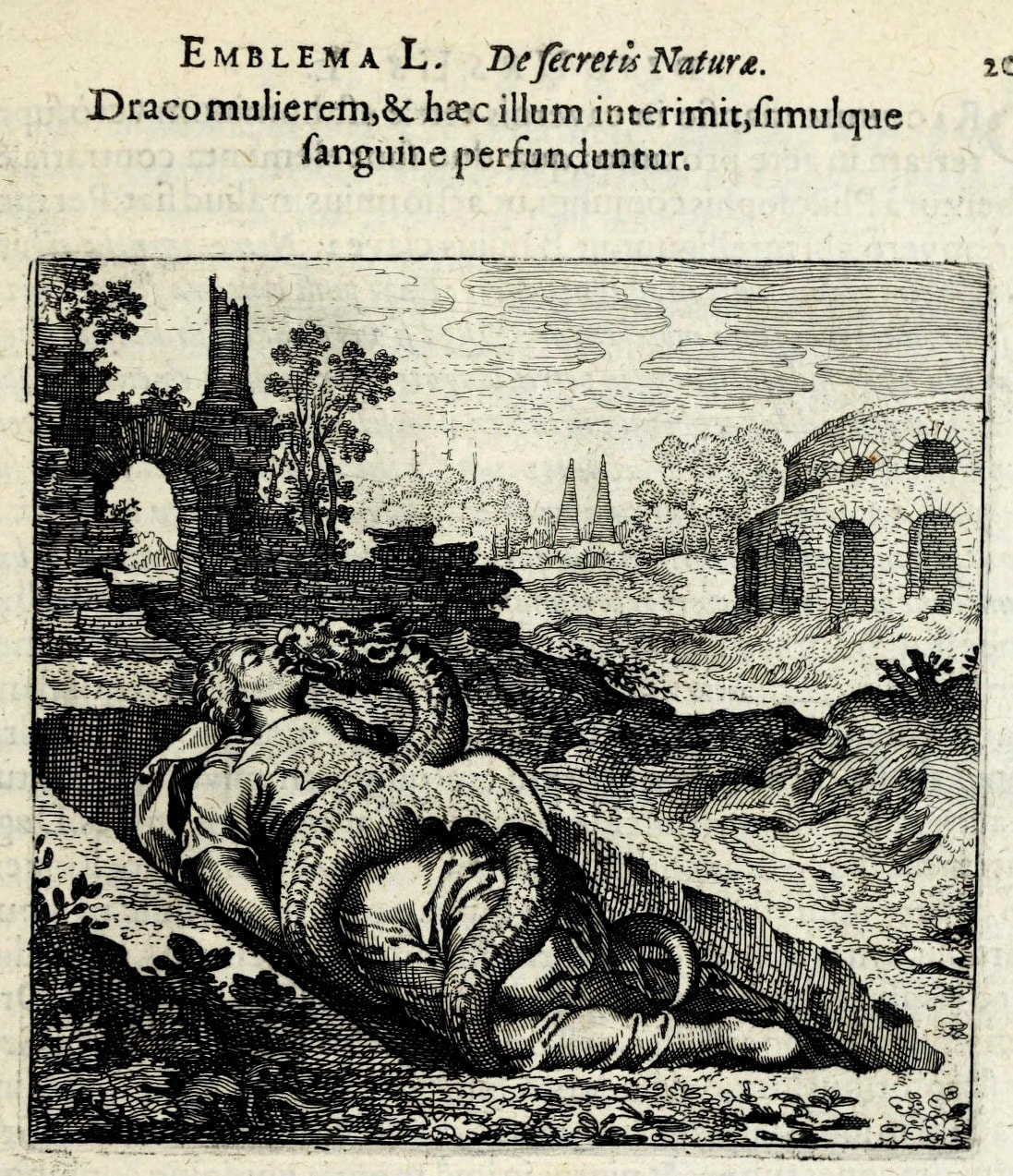

Two of Merian's illustrations from Atalanta Fugiens, an Emblem book published in 1618. Michael Maier wrote the text, and it was published by De Bry. In addition to epigrammatic poetry, prose, and illustration, it contained a musical fugue --making it one of the earliest forms of multimedia.

In an early example of the latter genre, he first developed his new style of capturing place in print: in his map of Paris the perspective hovers at a bird’s eye view, but it’s the view of a bird with a keen eye for architecture and who can read street names, as well.

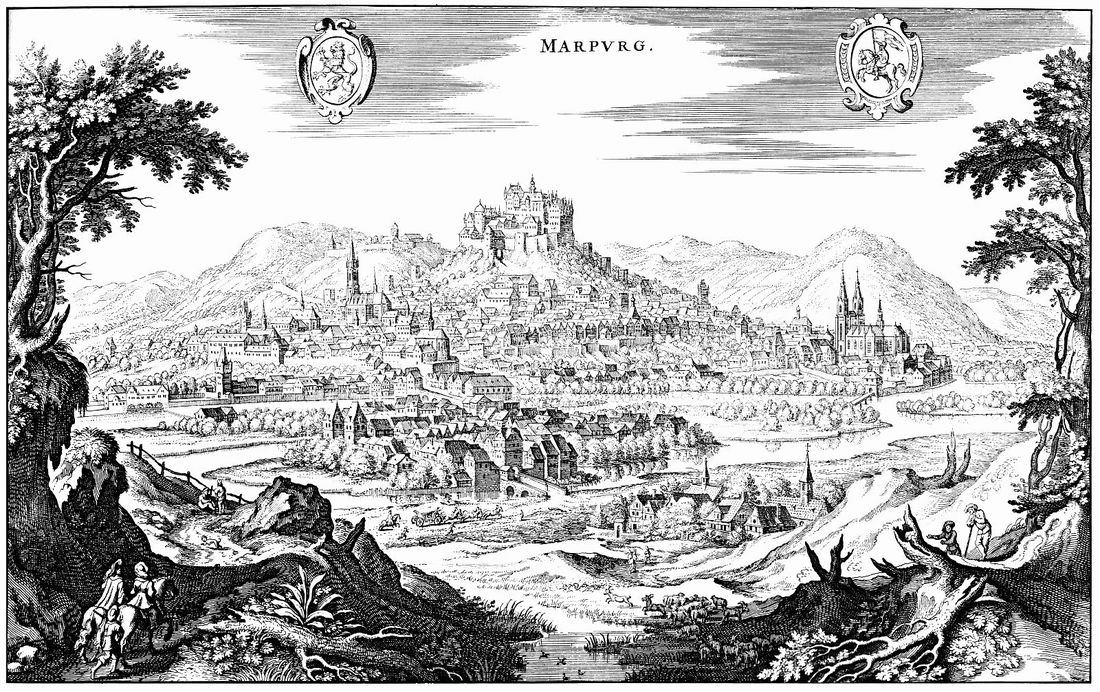

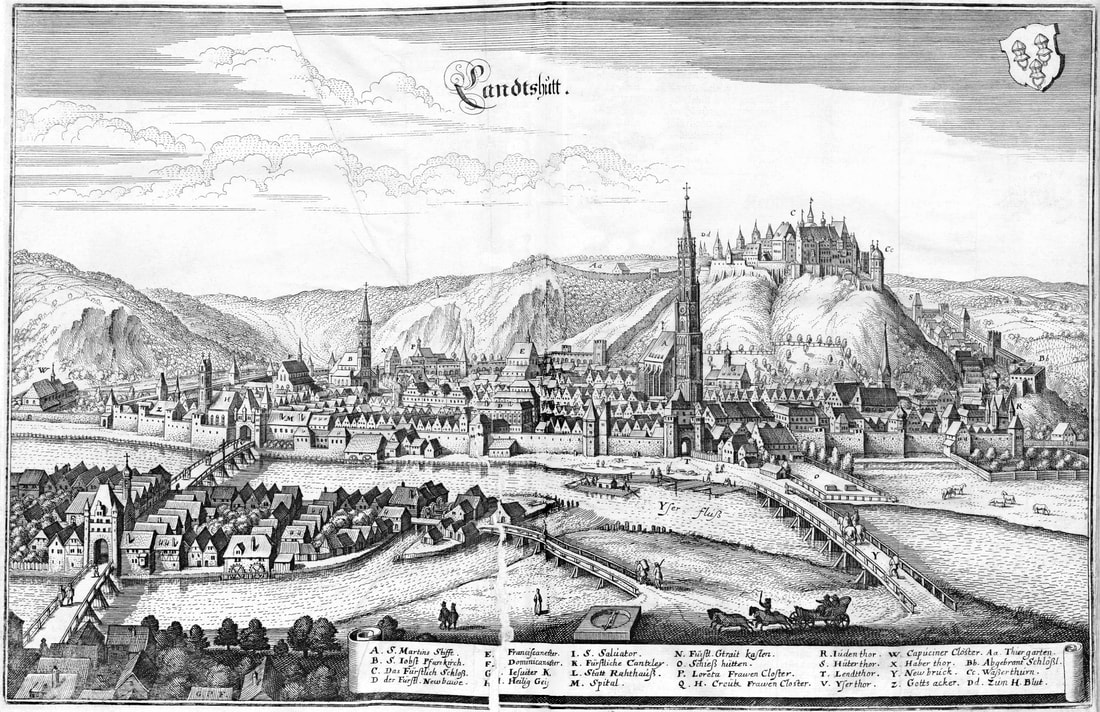

With a profitable publishing house established, Merian could begin his magnum opus. Each volume of Topographia Germaniae focused on a region of the Holy Roman Empire, either a political entity or a geographical region. Each volume would begin with a preface, briefly describing the history and culture of the place; it would be followed by an alphabetical listing of features both natural (rivers, mountains) and human (villages, landmarks). And then came the engravings: from the grand to the humble, cities were depicted in such detail, perspectives shifting from the cartographers to that of the passing traveler. Castles, monasteries, villages: all were depicted amidst their geographical landscapes, with a human or two going about their business.

It was (and still is) really kind of a stunning endeavor. The Topographia Germaniae amounted to an unprecedented effort to render a place in print, to provide a literal overview of a place. And it was indeed unprecedented: never before could a place be experienced from such a perspective. After the publication of this work, it became possible for the resident of some grand city in Bavaria or some little polity in Saxony to situate themselves: in the frame of an engraving, in the pages of a book, in the features of a landscape, in the polity of Empire, or in the geography of something even bigger and more abstract – something called Germaniae.

Plus, I find them delightful. Overview plus detail: it is a pleasure to trace the rivers, follow the ways, shade beneath trees and watch the skylines. Geography and architecture are married: humans have found a home.

There is another, poignant and significant fact about these city-engravings. Many of these cities had been destroyed or damaged beyond recognition during the ravages of the Thirty Years War. Merian himself repeatedly stated that his pictures often represented the condition of the "former bliss and glory" of a place, a glory which no longer existed – but could be rebuilt. The idealized images could serve as models for the new Germany, built from the ruins of the old (and not for the last time). The engraved image depicts the city that will come to depict the engraved image of itself – physically, in some cases, but certainly in the imagination and self-conception of its inhabitants.

Merian's depiction of of the sack of Magdeburg, utterly destroyed by the forces of the Catholic League in 1631.

And Merian's engraved reconstruction of the city.

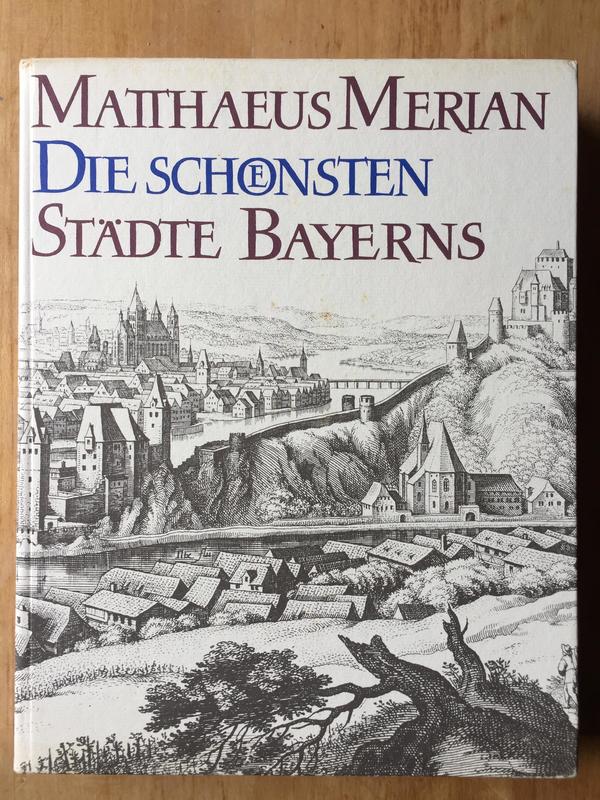

Merian died in 1650, before his work was completed. His sons Matthaus Jr. and Caspar continued the work, however, finishing it 1660. It was pirated and republished many times after that, culminating in the complete reissuing of the series by the publisher Bärenreiter-Verlag in the 1960’s.

I have a few of these volumes, some acquired online, and at least one from a bookseller at the foot of the Freiburg Minster.

One of the 30-volume republication of the Topographia Germaniae produced by Baerenreiter-Verlag in the 1960's.

Merian’s legacy lived on in another curious way. He had a daughter, Anna Maria Sibylla Merian, who became one of Europe’s earliest and most innovative entomologists, a passion which grew out of her skill in illustrating and engraving insects. For her (as with so many during the 17th century) the artist’s eye and the scientist’s were one an the same.