Rudolph's Alchemy, Part 2:

Roelandt Savery

One of the products of Rudolph II's alchemical court was an amazing catalog of paintings by a young Dutch painter who’d made the long journey east, drawn by Rudolph’s reputation: one Roelant Savery.

Savery must’ve been an attractive personality, for without much of a catalog to recommend him, he became Rudolph’s court painter.

Savery, by a contemporary Cornelius de Blie

To be a painter at the court of Rudolph II was to be more than a painter, however. Rudolph didn’t particularly hold to distinctions in disciplines: alchemy/chemistry, astrology/astronomy, science/magic/religion, painting and everything else…to be interested in the world was to be interested in the world.

And being palace-bound, Rudolph himself couldn’t get out and about as his interests suggest he’d have liked – so he saddled Savery with a quest: take a long field trip right through the Tyrolese, and take lots of pictures. Of everything. Document it all, and bring it back, where it can be packed away in the kunstkammerer and left to ferment.

Gather ingredients, in other words.

And so that’s what Savery did. He journeyed through the alps, sketching life (plant, animal, human) and landscapes (natural and man-made).

Rustic Building reflected in a Pool

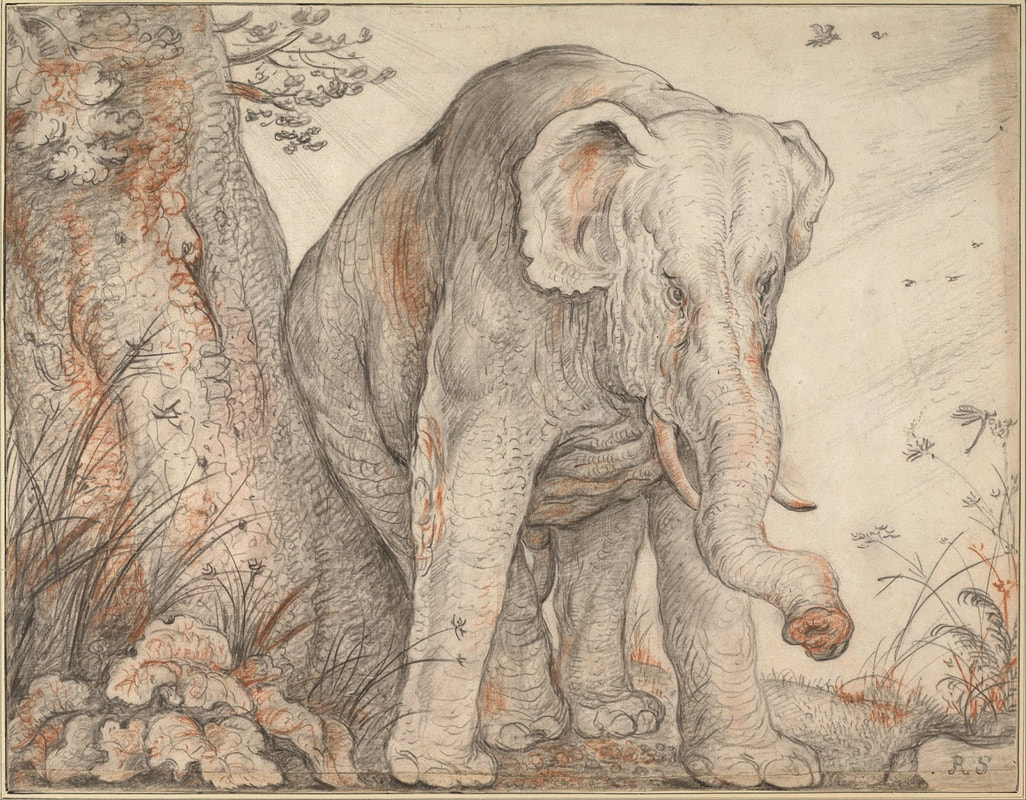

Upon his return to court he’d render these ingredients into his own concoctions – detailed-packed paintings of the various animals in Rudolph’s menagerie standing (often uneasily and looking rather out of place) in alpine landscapes thick with the plants he’d collected via his pen.

Landscape with Birds (1628)

The Paradise (1626)

He painted humans, fading in and out of a brand new Alpine landscape. (it might be worth writing an entry someday on the evolution of the Alps in the European imagination. They seem to have been variously invisible (blank impediments to mobility), vast terrifying wastelands of the early 18th century (as Defoe represents them in Roxana), or the sublime representations of deific immanence for the romantics. Or, as for Rudolph II, a storehouse of rare and rich ingredients).

Gebirglandschaft mit Reisenden (1608)

And in the process Savery sort of invented some new genres (or planted the seeds for, depending on your metaphor, and the more metaphors, the better. In the baroque mind of Rudolph II and his ilk, everything was metaphor).

Still Lifes, which were little alchemical productions of their own (the one below is crammed with 44 different species of animals and 63 species of flowers; can you spot ‘em all?).

Large Flower Piece with Kaiser's Crown (1624)

He also documented human brutality. Pillaging of a Village (1604) depicts a scene that was to become all too common during the Thirty Years War.

Savery had another unexpected influence upon the European imagination – an unintended side effect of his volatile creations. Rudolph must’ve collected a dodo bird for his menagerie (his Tierkammerer?). Because there it is, squatting awkwardly in a number of Savery’s own painted animal-collections. It is one of the first and one of the last depictions of a dodo, which went extinct shortly thereafter.

But Savery’s painting pickled and preserved the dodo for the human imagination, at least. There it is in one of Tenniel’s illustrations from Alice in Wonderland (a wunderkammerer of its own sort, really), and hence into the imagination of children…