Systema Naturae

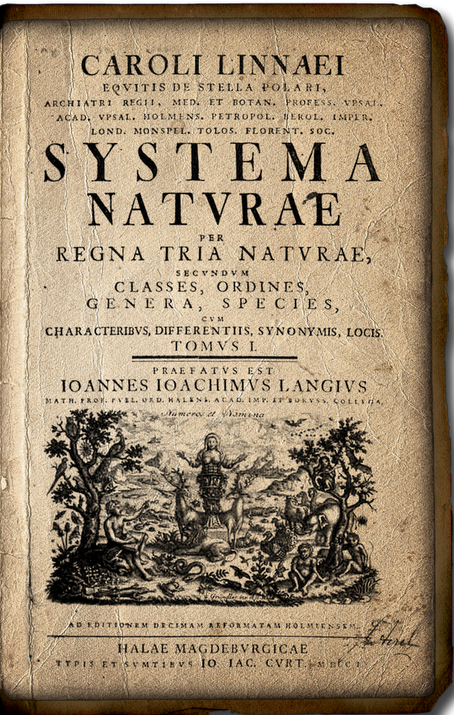

In 1735 Carl Linnaeus, son of a country minister from a small town in Sweden, published a book with an attention-grabbing title: Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.

|

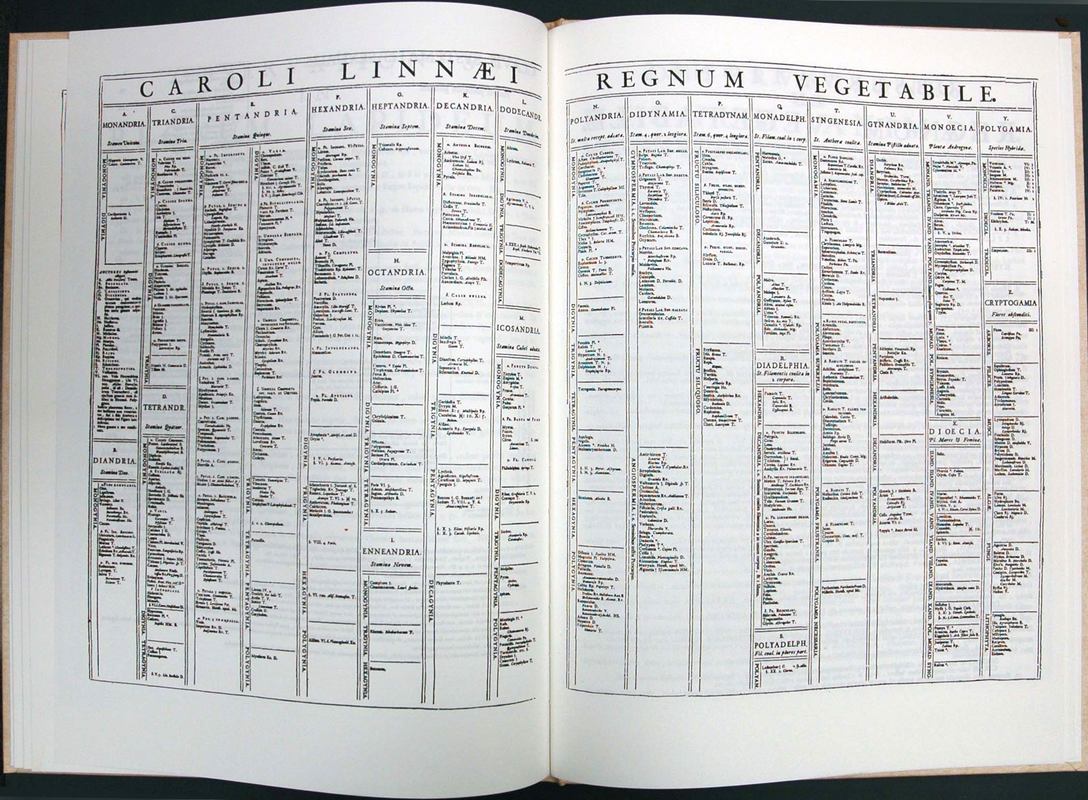

It was certainly a revolutionary book, in its way; it’s the book in which he elaborated and used consistently the system that we now refer to as binomial nomenclature. Things will be transformed by their names. As with the title of his book, names will now define things anew, creating a clunky, latinizing order on tangle and abundance – on life.

|

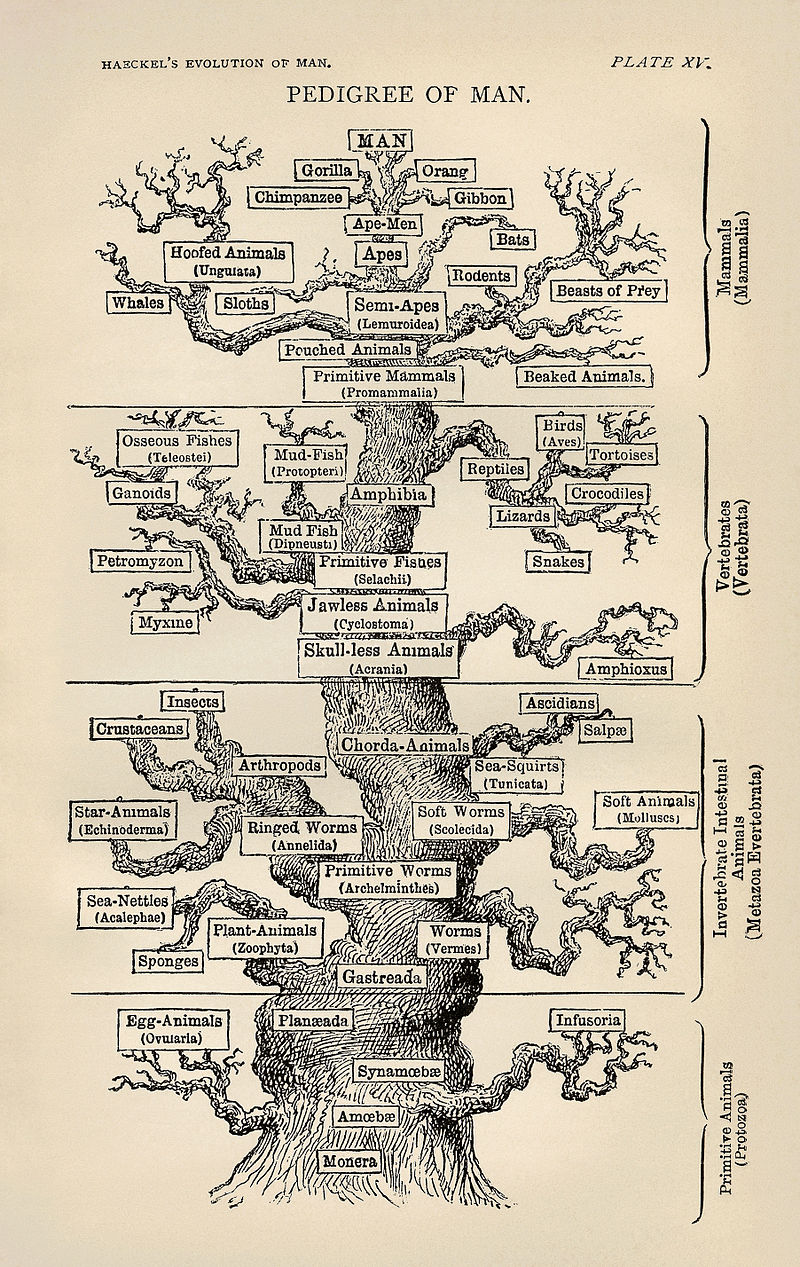

The book initiated a legacy that continues to define our relationship to the world. True, the system it laid out has been elaborated and refined over the centuries; it has been complicated by recent discoveries (different branches of his trees can interweave, graft themselves onto each other, tangling tidy family trees; see David Quammen’s recent book The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life, for instance). The trees of our understanding have grown and branches have divided themselves into the thinnest threads, but they still contain our world.

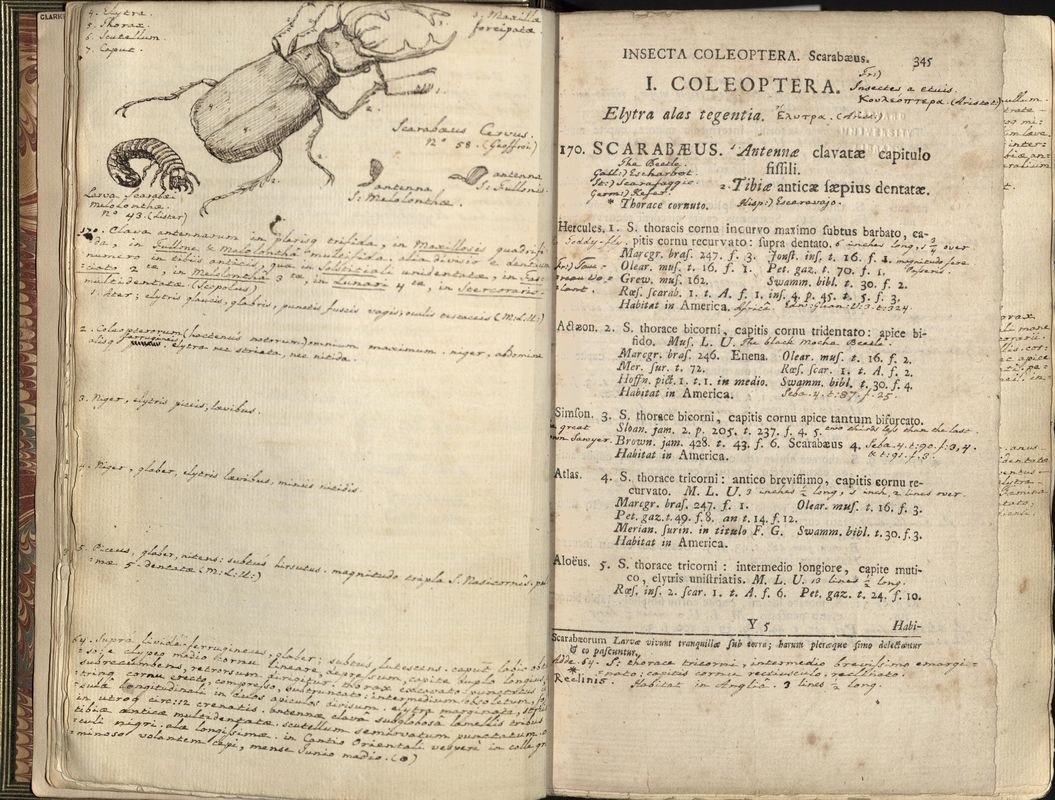

By 1735, of course, sketches and samples of a dizzying array of new life forms had been circulating throughout the salons and alchemical laboratories of the old world for a couple of centuries; wunderkammerer overflowed with stuffed specimens, pressed leaves and ornate seashells from new worlds. Of course some restless thinker, empowered by that new faith in the power of rational systems, should come along to impose some order on the jumble.

But it’s the first two words of the book’s title that fascinate me the most. (It’s the first two words of the book’s title, in fact, that have offered me the title of this essay, and the occasion to systematize the jumble of associations in my own imagination.)

But it’s the first two words of the book’s title that fascinate me the most. (It’s the first two words of the book’s title, in fact, that have offered me the title of this essay, and the occasion to systematize the jumble of associations in my own imagination.)

|

Systema Naturae: the title asserts, with all the insouciant audacity of those Enlightenment thinkers, that the universe can be understood. Not just the known universe: his book did more than just name existing creatures. By creating a system it proposed a means of understanding any and all future life forms that might be discovered – whether on some remote South American plateau, in a trench at the bottom of an ocean, or the dust of another planet.

|

|

Oh, man. The cool confidence of those 18th century philosophes, with their dictionaries ("we can fix language!") and encyclopediae ("a book containing…everything!"). I am nostalgic for the certainties their faith in reason afforded.

And while I can shake my head at the hubris of a title like Systema Naturae, I am also profoundly grateful to a system that, however biased and imperfect, allows me a glimpse of something vast, intricate, and of which I am very much a part: |