When reading The Iliad, my students often puzzle over the role of the Gods in the deeds of heroes and the events roiling around the walls of Troy. As have I. As has nearly every one. Occasionally the Gods appear on the battlefield physically, usually to ill-purpose or with comical results (as when Diomedes swats Aphrodite and sends her packing).

But most often, of course, they operate through individual humans (Diomedes is only able to beat Aphrodite, in fact, because Athena is working through him). Athena holds back Achilles’ arm when he’s about to strike Agamemnon, who’s just proclaimed he’ll have Achilles’ slave Briseis; Athena whispers to Achilles about a better way to obtain vengeance on Agamemnon, without jeopardizing the entire war against Troy. And Achilles, to the surprise of nearly everyone, lowers his arms and stalks off.

The careful, upstanding Hector, with so much to lose, is manipulated by Athena (the wise God, the manipulator of minds) into fighting a battle that he cannot win against Achilles, and Troy’s end is assured.

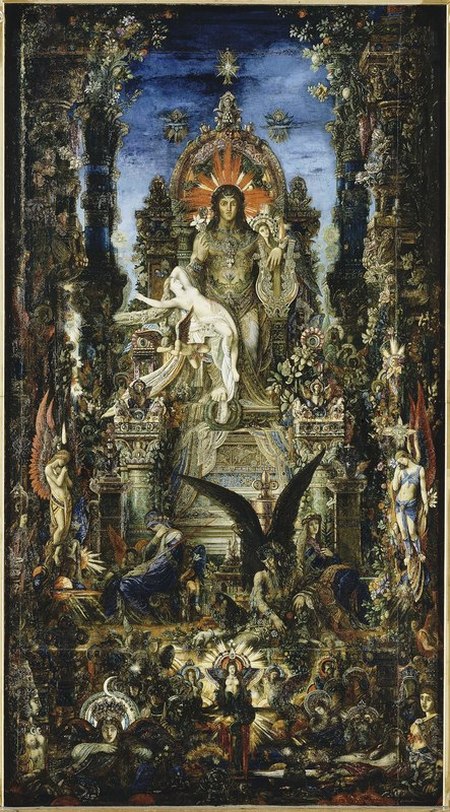

And so what relationship do Gods have to human action? To human decision making, and free will? Are they puppet masters, shaping circumstance and behaviors? Subtle manipulators, whisperers with still, small voices? Super human brutes, wading into the thick of human activities and dominating through their superior powers?

The careful, upstanding Hector, with so much to lose, is manipulated by Athena (the wise God, the manipulator of minds) into fighting a battle that he cannot win against Achilles, and Troy’s end is assured.

And so what relationship do Gods have to human action? To human decision making, and free will? Are they puppet masters, shaping circumstance and behaviors? Subtle manipulators, whisperers with still, small voices? Super human brutes, wading into the thick of human activities and dominating through their superior powers?

E. R. Dodds, in his magnificent old book The Greeks and the Irrational, argues memorably that the Gods appear in The Iliad to explain incomprehensible facets of human behavior. Why should Achilles act against his nature, playing the long inactive game of vengeance rather than opening Agamemnon up with a sword? Why should the careful Hector, who knows the value of his life to his city, suddenly engage the killing-machine Achilles after having evaded him for so long?

What, to that point, fills a warrior with the kind of irrational battle frenzy that might lead them to commit such brave, foolish and brutal deeds at all?

Human behavior is subject to tremendous, irrational forces: people do surprising, brilliant, foolish, horrendous and uncharacteristic things. The Gods in The Iliad (and elsewhere in Greek literature, Dodds argues) personify the mysterious, unpredictable powers in our own psyches to which we are subject. Their actions in the story allow characters to transcend the exigencies of Character, to become complex, contradictory, multi-storied: human.

What, to that point, fills a warrior with the kind of irrational battle frenzy that might lead them to commit such brave, foolish and brutal deeds at all?

Human behavior is subject to tremendous, irrational forces: people do surprising, brilliant, foolish, horrendous and uncharacteristic things. The Gods in The Iliad (and elsewhere in Greek literature, Dodds argues) personify the mysterious, unpredictable powers in our own psyches to which we are subject. Their actions in the story allow characters to transcend the exigencies of Character, to become complex, contradictory, multi-storied: human.

Myths, many of my students decide early on in the semester, grow up around forces that a) impact our lives profoundly, and b) remain utterly incomprehensible to us. The forces of nature, early on in the course of human development: the sky, the sea, the land, giving and taking. The echo of a voice against a cliff wall.

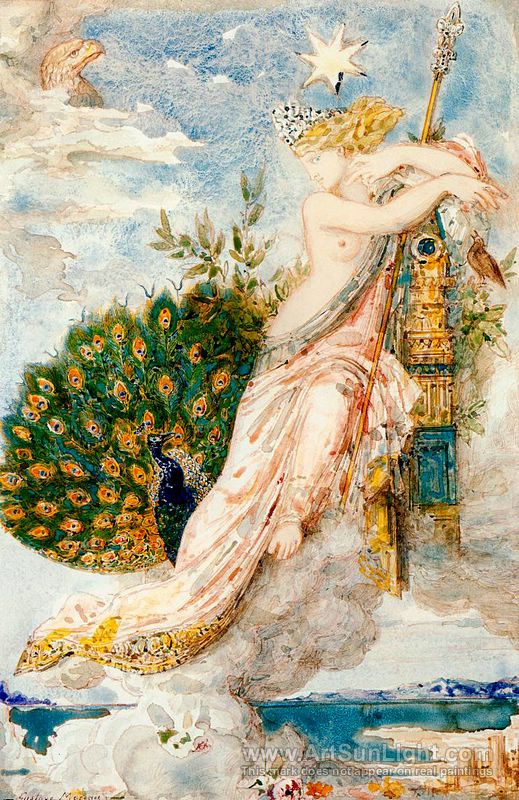

And later, as civilization develops, a second generation of Gods appears representing those forces of nature arrayed inside us: Love. The fear of death. The wiliness that lets a person elude her destiny, or the rage that can lead her to squander it

And later, as civilization develops, a second generation of Gods appears representing those forces of nature arrayed inside us: Love. The fear of death. The wiliness that lets a person elude her destiny, or the rage that can lead her to squander it

These second-order Gods, then: are they moods? Or are moods their handmaidens? A feeling that comes over us, transforming our perception of everything. The moods reorganize our relationships – with our selves, with others, with the world.

|

At a tricky point in his life, W. B. Yeats wrote a story literalizing this idea: a mood as inhabitation by divinity. “Rosa Alchemica” was part of a triumvirate of tales exploring the occult, written before the middle-aged Yeats was revivified by his meeting with Ezra Pound, and performed his subsequent remarkable self-transformation into a Modern poet. “Rosa Alchemica” is not modern. It is a looking back, a scrupulous effort to plant secrets in the past, in old volumes and forgotten rituals, ancient philosophies and epistemologies, and then unearth them. It is an effort to create an occult history, and then trace its effect on the living world. In the story, Michael Robartes (that marginal figure flickering in and out of Yeats’ work) initiates the narrator into an ancient ritual, the purpose of which is to rend the veil between this and the divine realms. In an isolated and run-down house in the wild West of Ireland, a carefully contrived dance is enacted. Watching the dancers, the narrator begins to notice others, shimmering figures that take up the dance and its steps, partnering with the mortal dancers and transforming the dance. Here is how these figures are described, as laid out in the story’s sacred (secret) book, Splendor Solis: The bodiless souls who descended into these forms were what men called the moods; and worked all great changes in the world; for just as the magician or the artist could call them when he would, so they could call out of the mind of the magician or the artist, or if they were demons, out of the mind of the mad or the ignoble, what shape they would, and through its voice and its gestures pour themselves out upon the world. In this way all great events were accomplished; a mood, a divinity, or a demon, first descending like a faint sigh into men's minds and then changing their thoughts and their actions until hair that was yellow had grown black, or hair that was black had grown yellow, and empires moved their border, as though they were but drifts of leaves. |

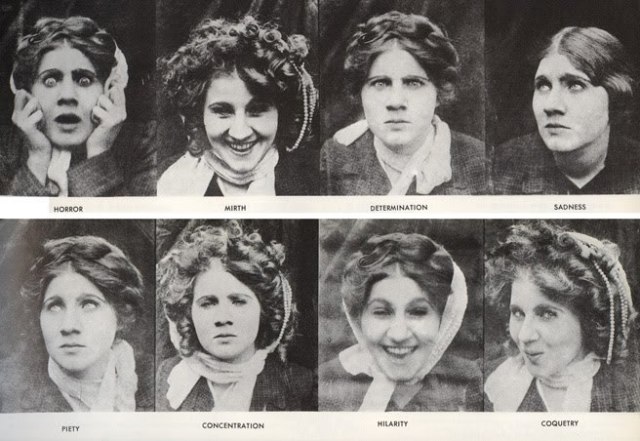

Elena Makowska's demonstration of her ability to become inhabited by the Moods!

So what does it mean to be called “moody?” Since I was a kid I’ve been subject to the sometimes harsh transformational alchemies of mood. Of all the transformational powers out there, the Moods are the most immediate. Religion promises such transformations of self, as does the good old Protestant work ethic. Self-help charlatans and neuro-chemists have built industries around the desire for self transformations. Addictions flourish where these efforts fail, or are too daunting.

And against all these culture-wide efforts to transform our outlook (and inscape): the simplicity of a mood. Teetering on the edge of despair, or surveying the lifeless flats of ennui or existential vacancy (where fierce and predatory moods stalk), the right song can bring deserts to life. The passing scent of some bouquet in the house of an old girlfriend. The cast of late afternoon sunlight against my window. The corkscrew chase of two squirrels down a tree-trunk.

The ability to master one’s moods would be a superpower indeed. But then, I suppose, they would not be moods. The Gods cannot be mastered, after all, and that is where their power lies. Michael Robartes’ initiates can dance, but those bodiless souls that inhabit them will do so of their own accord.

I guess my poor old Grandmother never thought about this when she’d tell me a little impatiently to perk up…

And against all these culture-wide efforts to transform our outlook (and inscape): the simplicity of a mood. Teetering on the edge of despair, or surveying the lifeless flats of ennui or existential vacancy (where fierce and predatory moods stalk), the right song can bring deserts to life. The passing scent of some bouquet in the house of an old girlfriend. The cast of late afternoon sunlight against my window. The corkscrew chase of two squirrels down a tree-trunk.

The ability to master one’s moods would be a superpower indeed. But then, I suppose, they would not be moods. The Gods cannot be mastered, after all, and that is where their power lies. Michael Robartes’ initiates can dance, but those bodiless souls that inhabit them will do so of their own accord.

I guess my poor old Grandmother never thought about this when she’d tell me a little impatiently to perk up…