Internal Designs

Architecture doesn’t just organize physical space; it can be a pretty powerful force for organizing psychological space.

It is a function of architecture that is at least as old as civilization itself: as far back as the Ziggurats of Ur political power has expressed itself in architecture. The design of palaces, temples, and public buildings are not just expressions of a culture’s values; they actively shape the psyches of those who enter them.

In absolutist ages, interiors of palaces can be designed to concentrate power within a single body – that of the monarch.

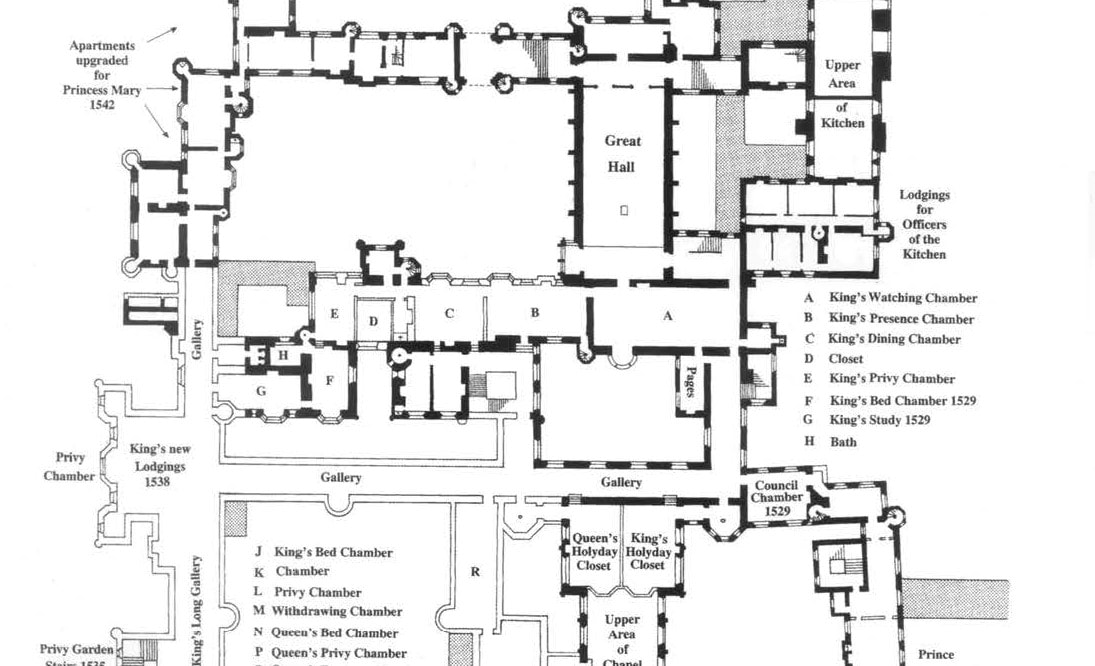

At Hampton court, for instance, those who sought audience with Henry VIII or his successors were asked to wait in a series of successively smaller, more intimate and ornately decorated chambers. Only a few would be admitted into the next chamber, and fewer still into the next. By the time whatever individual was privileged enough to obtain the presence of the monarch did so, he or she would be facing the entire weight and wealth of the palace, all concentrated onto one body.

It is a function of architecture that is at least as old as civilization itself: as far back as the Ziggurats of Ur political power has expressed itself in architecture. The design of palaces, temples, and public buildings are not just expressions of a culture’s values; they actively shape the psyches of those who enter them.

In absolutist ages, interiors of palaces can be designed to concentrate power within a single body – that of the monarch.

At Hampton court, for instance, those who sought audience with Henry VIII or his successors were asked to wait in a series of successively smaller, more intimate and ornately decorated chambers. Only a few would be admitted into the next chamber, and fewer still into the next. By the time whatever individual was privileged enough to obtain the presence of the monarch did so, he or she would be facing the entire weight and wealth of the palace, all concentrated onto one body.

|

Here is a section of the floorplan at Hampton Court. The chambers I’m referring to here are labelled A through G. The bedchamber wasn’t where the king slept; its function was ceremonial (and psychological) – only the most privileged courtiers and the king’s own privy council would be allowed such intimate access to the royal person.

(I rather enjoy the fact that the only bathroom (H) was there, next to the innermost chamber. Nothing like a little gastric discomfort to establish the monarch’s authority…) |

And the King's Presence Chamber

This is the appropriately named Great Watching Chamber (A, on the plan above).

|

At Versailles, of course, Louis XIV refined the capacity of a building to brutalize its inhabitants through formality and splendor. The unlucky aristocrats fortunate enough to bask in the king’s presence were subjected to a deliberate architectural sundering of public and private selves. An aristocrat’s private quarters, after all, were small, poorly lit and unventilated. In the king’s public space, then, a courtier would enjoy all the gaudy, gilded magnificence that the late Baroque could bring to bear – and then they’d return to freeze in their unventilated warrens.

I've written elsewhere (here and here, to be precise) about the use of castle-reconstruction in 19th century Germany to shape a national identity. Hereditary castles could be reconstructed as public monuments (as was burg Hohenzollern) or private fantasies (Neuschwanstein, of course). Or, as with Hohenschwangau, a building could be designed that sought to reconcile public and private identities, poetic and historical identities.

For all it's kitsch and touristy appeal, Hohenschwangau really does redeem the public building from the assertive manipulations of other royal residences. It attempts, at least, to reconcile the public and private roles of its inhabitants. In this, it aspires, at least, to achieving that romantic ideal of a unified self.

For all it's kitsch and touristy appeal, Hohenschwangau really does redeem the public building from the assertive manipulations of other royal residences. It attempts, at least, to reconcile the public and private roles of its inhabitants. In this, it aspires, at least, to achieving that romantic ideal of a unified self.

But for me, it's William Morris who does the most to establish a collaborative relationship between self and space.